Luke came out as trans when he was 11, hoping to start hormone therapy as a teenager. Instead, he was held hostage in a political and medical battle that's far from over. caitmosc reports

Luke, 18, is one of thousands of young trans people in the U.K. whose care has been delayed. Photo: Olivia Arthur/MAGNUM PHOTOS This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

“I was in an absolutely terrible place because I couldn’t cope with waking up and things being the same every single day,” Luke says. He socially transitioned at age 12, the same year he was diagnosed with gender dysphoria. He has been binding his chest for so long that he barely thinks about it anymore. To boost his five-foot-four frame, he often walks in black lace-up boots with a chunky heel.

As the lawyers and legislators fight, countless gender-diverse young people are caught in the middle. Without access to blockers, some of them are forced to go forward with a puberty that doesn’t align with their gender, producing irreversible changes that can only be corrected with painful and expensive surgeries later on. In the meantime, governments and health authorities seem further than ever from reaching a consensus on the best kind of care for trans kids.

He eventually decided he wanted to be called Luke and use male pronouns. His father covered up a tattoo on his hand of the name they’d given Luke at birth, which Luke saw as an act of love. “He’s not superemotional, but that was his physical action, like, showing a lot of acceptance,” he says. To cope, Luke tried to alter his body on his own. He began binding his chest, first using “really rubbish” binders he’d ordered on Amazon before finding one that didn’t hurt quite as bad. He Googled ways to deepen his voice, none of which worked, and lifted weights in the hopes of broadening his shoulders. He began menstruating, and his depression worsened. “I was getting really desperate,” he says.

Photo: Olivia Arthur / Magnum Photos While Luke waited years to be seen by GIDS, a rift was developing within the organization. In 2014, the service’s leadership adopted the protocol developed in Amsterdam, but some clinicians objected that GIDS was pushing patients toward blockers and hormones too quickly. They began voicing their concerns internally, arguing for a greater commitment to therapy for patients with gender dysphoria.

Anastassis Spiliadis, a psychotherapist and psychoanalyst who worked at GIDS from 2015 to 2019, says that at times, he felt like “the only thing that the service was offering was a medical approach.” Spiliadis was alarmed when, he says, Carmichael told clinicians not to bring their concerns to the service’s child-safeguarding lead.

In the summer of 2018, Bell wrote a report on the clinicians’ concerns and submitted it to the Tavistock Council of Governors. “Dr. Bell kind of ran away with it and wrote a report that was full of his own criticisms,” says Wren. He used “very, very extreme language, implying senior staff were harming children.”

Still, the pills “didn’t make everything okay,” he says. Luke got upset looking at photos of himself before puberty, when his body was “genderless,” what he describes as a blank canvas — when “it could have gone another way, but it didn’t.” He stopped going to gym class. He avoided parties. As his classmates started to look more like adults, Luke oscillated between two states of panic.

When two GIDS clinicians came in to talk with Luke and his mother, he expected that they’d quickly go through his history and start discussing medical options. Instead, “it was a very kind of vague check,” says Luke. “They were just like, ‘How old are you? How do you feel? When do you feel it?’ ” Most of the questions focused on the past year — if he’d felt more like a girl or a boy, if people treated him like a girl or a boy, if he felt his life would be better as a boy.

By the third appointment, emotions were running high. One of the forms he was told to fill out asked if Luke thought of himself as a hermaphrodite, which he found offensive and outdated. He was similarly upset when a clinician challenged him on why he had never had a romantic relationship. Luke explained that he was too uncomfortable in his body to connect with another person on that level.

Bell’s report found two strong supporters in Susan Evans, who had a short tenure at GIDS in the mid-aughts, and her husband, Marcus, a member of the Tavistock Council of Governors who resigned because he didn’t think the organization was taking Bell’s recommendations seriously. They soon mounted a public campaign to sound alarms about GIDS. In their view, there was not enough evidence to support putting young people on blockers.

Keira had her first appointment with GIDS when she was 15, and she says that by the time she got there, she was “adamant that I needed to transition.” After what she describes as “a series of superficial conversations with social workers,” she was put on puberty blockers at age 16 and received her first testosterone shot a year later. Her voice deepened, she grew facial hair, and she changed her name to Quincy. At 20, she had her breasts removed.

In their decision, the judges wrote that it was “highly unlikely” a child 13 or under could give informed consent to puberty-blocking treatment and that they were “very doubtful” children 14 or 15 could do so either. The judges seemed particularly skeptical that a child under 16 could understand the way puberty blockers might affect their fertility and sexual functioning.

Because Luke had just turned 17, he wasn’t initially affected by the court’s decision: He had been on blockers for more than three months by the time Bell v. Tavistock was announced. He was relieved that he would be able to continue them, but he knew people who were still waiting. Most of them would likely pay for private health care, he believed.

In the end, he stayed on blockers — less a choice than a necessity. To help with the side effects, his endocrinologist suggested they try reducing the interval between doses. “I’ve been on them for so long I’ve been getting really, really bad pain in my bones, in my muscles, and getting a lot of skin pain,” says Luke. “It’s affecting my sleep.”

Ireland Latest News, Ireland Headlines

Similar News:You can also read news stories similar to this one that we have collected from other news sources.

Michael Buble, Placebo and Machine Gun Kelly Battle For U.K. No. 1 AlbumThe Canadian crooner’s aptly-titled album “Higher” (Reprise) leads the midweek U.K. chart.

Michael Buble, Placebo and Machine Gun Kelly Battle For U.K. No. 1 AlbumThe Canadian crooner’s aptly-titled album “Higher” (Reprise) leads the midweek U.K. chart.

Read more »

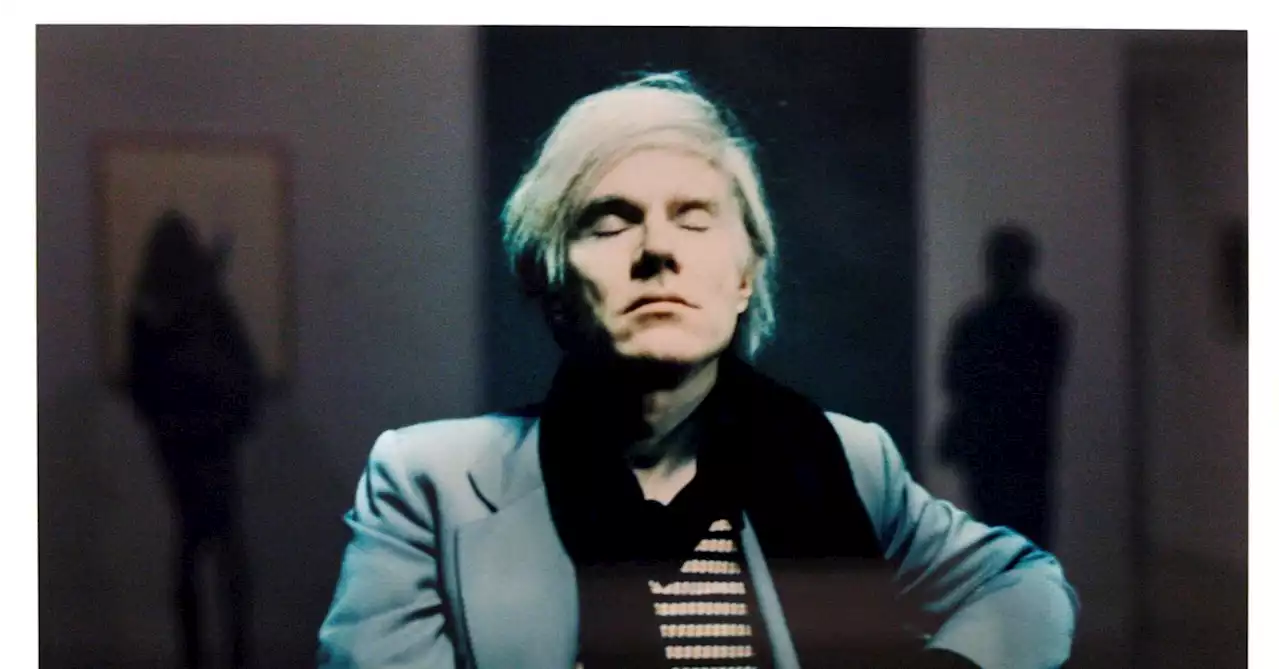

U.S. Supreme Court takes up copyright battle over Warhol's Prince paintingsIn a case that could help clarify when and how artists can make use of the work of others, the U.S. Supreme Court on Monday agreed to decide a copyright dispute between a photographer and Andy Warhol's estate over Warhol's 1984 paintings of rock star Prince.

U.S. Supreme Court takes up copyright battle over Warhol's Prince paintingsIn a case that could help clarify when and how artists can make use of the work of others, the U.S. Supreme Court on Monday agreed to decide a copyright dispute between a photographer and Andy Warhol's estate over Warhol's 1984 paintings of rock star Prince.

Read more »

Trans Texans still on edge after state’s investigations put on holdThe Texas Department of Family and Protective Services last reported there were nine gender-affirming care cases open since the governor’s directive to the state on February 22.

Trans Texans still on edge after state’s investigations put on holdThe Texas Department of Family and Protective Services last reported there were nine gender-affirming care cases open since the governor’s directive to the state on February 22.

Read more »

U.K.’s Top Court Withdraws Judges Presiding in Hong Kong, Citing Loss of Freedoms in CityTwo top U.K. judges serving on Hong Kong’s highest court have resigned, citing damage to freedoms in the city following Beijing’s imposition of a national security law in June 2020

Read more »

Laws Vilifying Transgender Children and Their Families Are AbusiveRecent measures in Florida, Texas and elsewhere serve to traumatize trans children and their families, uphold ideas that trans children are inherently troubled, and go against medical advice

Laws Vilifying Transgender Children and Their Families Are AbusiveRecent measures in Florida, Texas and elsewhere serve to traumatize trans children and their families, uphold ideas that trans children are inherently troubled, and go against medical advice

Read more »