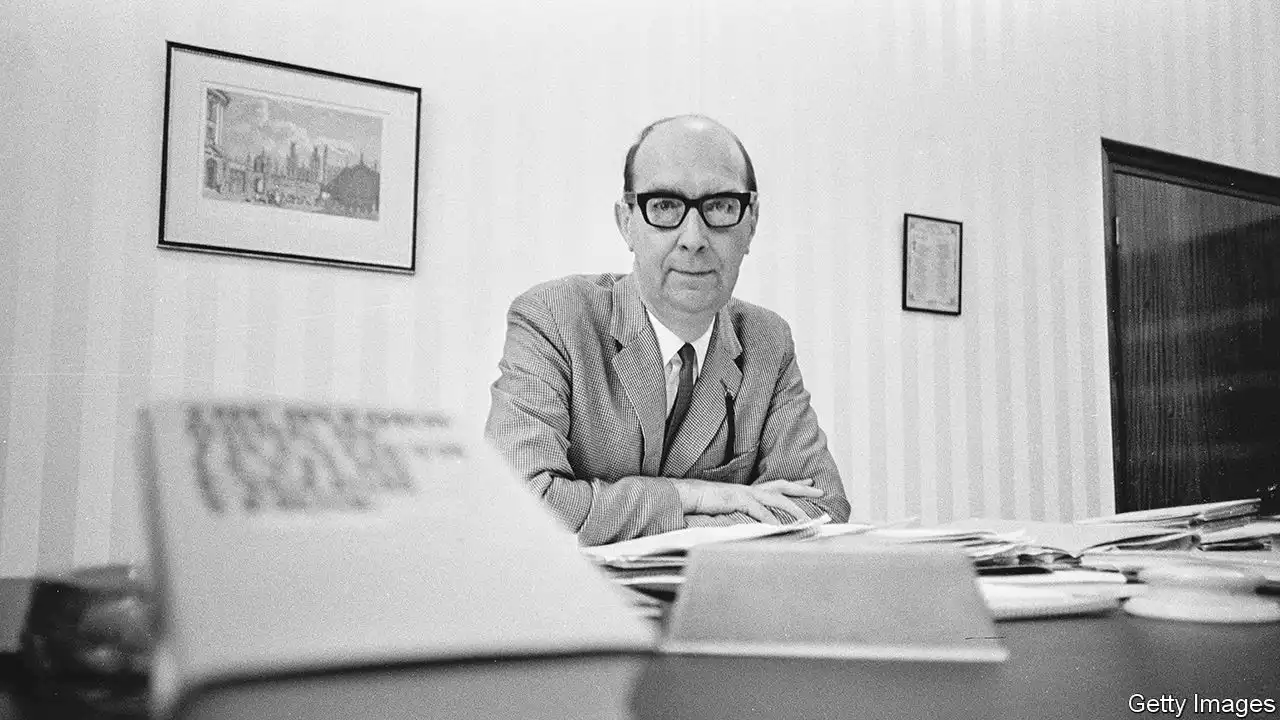

When Philip Larkin’s letters were published in 1992, they exposed a seam of racism and misogyny, as well as a childishness at odds with the grave craftsmanship of his finest verse

Save time by listening to our audio articles as you multitaskBut Larkin is more than just the unofficial laureate of humdrum Englishness. His poems, rather than practising the British habits of evasion and whimsy, speak directly. Many begin with bracing immediacy: “I work all day, and get half-drunk at night”; “I deal with farmers, things like dips and feed”; “The mower stalled, twice; kneeling, I found/A hedgehog jammed up against the blades.

Yet often his manner is less jaundiced than tender. He notes the “miniature gaiety of seasides”, pictures the sun’s “petalled head of flames” and addresses a newborn child as “Tightly-folded bud”. Expressing himself sparely, he zeroes in on physical details that are tellingly ugly or bluntly unpoetic. One of his best poems, “The Whitsun Weddings”, itemises what he sees while travelling by train on a hot Saturday afternoon , and in so doing builds to an unexpected, transcendent climax.